Details:

Ex parte Toyomura

Appeal 2010000963; Appl No. 10/010,630; Tech. Center 2100

Decided: August 8, 2012

The application on appeal was directed to a memory card that handled different types of files by storing files in different format-specific directories, and by storing all files of non-supported formats in a separate directory. The application claimed priority to several Japanese applications.

As originally filed, claim 1 read:

1. Carryable memory media comprisingIn the first response, the Applicant amended. In doing so, "form" was changed to "format":

at least one directory for storing specific format files, which files have a certain predetermined form, and

a directory for storing non-specific format files, which files having any free form.

1. A memory media comprisingDuring prosecution, the Applicant further narrowed to overcome a § 101 rejection and to distinguish over the art:

a plurality of directories at a directory level, each of said directories limited to storing files of a respective one of a plurality of file formats, and

a further directory at said directory level, said further directory for storing files in other than said plurality of file formats.

1. A memory media for storing data for access by an application program being executed on a data processing system, the memory media comprisingThe Examiner rejected several independent claims as being anticipated by Andro. By way of explanation, the Examiner noted that Andro stored all video files in a video subdirectory and all audio files in an audio subdirectory.

a plurality of directories at a directory level, each of said directories limited to storing files of a respective one of a plurality of file formats, so that not more than said respective one of said plurality of file formats are permitted to be stored in each of said directories and

a further directory at said directory level, said further directory for storing files in other than said plurality of file formats.

(Emphasis added)

The Applicant appealed. The argument in the Appeal Brief was basically about the meaning of "file format":

[T]his means that each one of the plurality of directories is limited to storing files having one format. Example directories are shown [in the schematic below]Then in the Reply Brief, the Applicant argued that the Examiner had confused the reference's file types with the claim's file formats:

Directory Level

---- doc

---- xls

---- xlm

--- other

As shown, a a first directory can only store .doc files. A second directory can only store .xls files. ...

Audio files, for example, have different formats. Exemplary formats include WAV files, MIDI files, WMA (Windows Media Audio) files, MP3 files, etc. Video files can also have different formats. Exemplary video files include Blu- ray, HD-DVD, MPEG3, MPEG4, etc. Appellants' claims are clear that each directory is limited to one format (e.g. MP3, MPEG4, etc.). Appellants' claim 1 does not claim that each directory is limited to one type of file (e.g. audio or video).The Board found that that Applicant's interpretation of "file format" was not supported by the specification. The Board noted that the very portion of the specification referred to in the Appeal Brief "Summary Claimed Subject Matter" read:

The directory group 8 for storing specific format files comprises a directory 6 for storing music files, a directory 7 for storing still image files and other directories (not shown).The Board found that the specification was "more consistent with the Examiner's interpretation of the claimed invention and contradictory to Appellants' arguments in the Reply Brief." The Board therefore affirmed the rejection.

MP3 and the like files of music file format, for example, are stored in accordance with the directory 6 for storing music files in a corresponding data area. Exif and the like still image files are stored in accordance with the directory 7 for storing still image files in a corresponding data area. Meanwhile, no specific format files are stored in accordance with the directory 9 for storing non-specific format files in a corresponding data area.

(Emphasis added.)

My two cents: I've seen plenty of cases where the Board doesn't adopt a claim term interpretation urged by the Applicant. But usually it's one where the Applicant tries to narrow based on stuff in the spec, and the Board refuses to "import limitations from the spec." I don't think I've ever come across this scenario before, where the specification so fundamentally at odds with the Applicant's position on appeal.

Based solely on plain meaning, the Applicant's description of "format" sounds about right to me: file format is WAV, MP3, Blu-Ray, etc. whereas file type is video or audio.

Yet when I read paras. 44 and 45 of the specification (relied on by the Board), I lean the other way and think: multiple formats of audio files are stored in a single audio directory.

At first I wondered if the Applicant's spec should have done a better job of distinguishing between file types and file formats. I see some overlap in the terms, so I can kinda see where the Examiner is coming from.

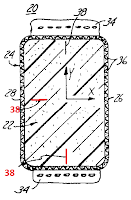

But then I looked at FIG. 1 of the Applicant's spec:

To me, FIG. 1 clearly shows that the inventor contemplated the Examiner's interpretation rather than the one advanced by the Applicant on appeal.

I see no way to reconcile FIG. 1 of the originally filed spec with the schematic directory representation submitted by the Applicant in the brief:

Directory Level

---- doc

---- xls

--- xlm

--- other

Unless translation from Japanese to English caused the problem? After all, it was a translator who decided on the sentence "The directory group 8 for storing specific format files comprises a directory 6 for storing music files, a directory 7 for storing still image files and other directories (not shown). As is common with patent applications, the text in FIG. 1 corresponds almost exactly to that in the specification's description of FIG. 1.