Details:

Milan v. Apple

Appeal 2012008569; Reexamination No. 95/001,083; Tech. Center 3900

Decided Aug. 7, 2012

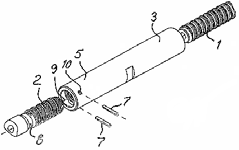

The patent under reexamination described a flash memory device designed for use with a set of converter plugs. As shown in the figures below, the pin configuration (416) on the flash memory device (400) was configured to mate with several different converter plugs, including a 4-pin USB plug (FIGs. 12A-C) and a 5-pin mini-USB plug (FIGs. 12A-C).

The Patentee appealed various rejections, including independent claim 1 as obvious over two non-patent references ("Palm V Handbook Travel Kit" and "Handbook for Palm Tungsten Handhelds"), and dependent claim 3 as obvious over Palm, Tungsten, and Sirichai.

1. A flash memory device comprising:

a housing having opposed first and second ends;

a flash memory drive enclosed in said housing; and

a quick connector mounted in said housing and having a plurality of pins exposed at said second end, said pins being configured for electrical connection to a selected one of at least a first interchangeable connector and a second interchangeable connector ...

3. The flash memory device according to claim 1 wherein said plurality of pins is six female pins arranged in two parallel rows of three pins each.

After rejecting independent claim 1 as obvious over the combination of Palm and Tungsten, the Examiner added Sirichai and used the substitution rationale to reject dependent claim 3. In rejecting claim 3, the Examiner made several findings of fact, including the ones discussed in MPEP § 2143(B) for the substitution rationale:

- One type of Firewire connector is known to have a six pin configuration arranged in two parallel rows of three pins each.

- The prior art (Palm combined with Tungsten) contained a device which differed from the claimed device by the substitution of one component (Sirichai's connector) for another component (Palm's connector).

- Sirichai disclosed USB connectors and Firewire connectors, and described them as known equivalents.

- A POSITA could have substituted one known element (Sirichai's Firewire connector) for another (Palm's USB connector), and the results of the substitution would have been predictable.

The Patentee attacked the obviousness rejection of claim 3 by disagreeing with the Examiner's finding that Sirichai taught the equivalence of USB and Firewire connectors. According to the Patentee, Sirichai's discussion of lighted electrical connectors instead taught that:

... the connector tip is a USB connector tip and in another embodiment the connector tip may be a firewire connector tip. The connector tip 150 of Sirichai is simply referring to "an opaque metal shell[.]" Sirichai only provides that both USB and firewire connector tips could utilize the light source disclosed; it does not disclose that the pin configuration, the wiring scheme required or operation of the two are equivalent.

(Emphasis added.)

The Patentee then concluded that "simply substituting the USB connector of Tungsten with the connector body for a firewire connector will not result in functionality of the resulting connector" and as a result, the combination would not result in claim 3.

The Board was not persuaded by the Patentee's "no equivalence" argument. According to the Board, "a teaching of such equivalence is not required" to support the substitution rationale described in KSR. The Board found that the Examiner had made the requisite findings of fact for a substitution rationale, and the Patentee had not demonstrated error in these findings. The Board therefore affirmed the rejection of dependent claim 3.

My two cents: The Board reached the right result -- at the level of detail expressed in the claim, it is obvious to substitute a USB (serial) connector for a Firewire (parallel) connector. Yes, the operation of a serial bus and a parallel bus is different. But none of those differences have anything to do with what's in the claims. Yes, the pin configurations and wiring schemes are different. Nonetheless, substituting one connector for the other is within the knowledge of a POSITA, and the Applicant didn't argue otherwise.

I do have a problem with the Board's statement about findings of equivalence, because I think it's misleading. Of course the claimed feature and the substituted feature from the reference aren't required to be equivalent in every way. But the two must be equivalent at some level, otherwise you couldn't substitute one for the other, right?

And you can fight an obviousness rejection on this point, i.e., by explaining the differences and why the reference feature wouldn't act as a substitute for the claimed feature. Maybe the lesson here is not to characterize such an argument as being about equivalence, but instead to couch it in terms of "results would not have been predictable" (i.e., the third finding mentioned in the MPEP discussion of substitution)?

I have a problem with this too, however, as the results of a badly-conceived substitution are probably quite predictable: the combination doesn't work as intended, or work as well, or too many modifications are needed to consider it obvious.

So to me, it is about equivalence, not predictability. Because it makes sense to argue that a POSITA would not substitute a blodget for a widget because they are not equivalent in these specific ways which relate to what is claimed. The Patentee here didn't win because he didn't (or couldn't convincingly) explain why the differences matter for what is claimed, and/or why the differences were too great for a POSITA to handle.